Social behaviour change communication objectives

SBCC may be used to influence parents and caregivers to adopt the World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) recommended IYCF behaviours. However, a common criticism of nutrition campaign messages is that they often focus on simply providing information rather than engaging audiences in more compelling ways. Information alone is often not enough to change behaviour.

Developing and framing emotionally engaging messages to resonate with audiences and implementing creative activities may add value to campaign development. For example, by combining campaign messaging and community mobilisation activities, caregivers are encouraged to trial and adopt improved IYCF behaviours that are achievable, important and contextually relevant.

The 2020-2025 SADC Regional Social Behaviour Change Communications Strategy suggests that campaigns should aim to raise awareness, build knowledge, and change attitudes and perceptions. Examples include:

- Optimal infant and child dietary practices promote health and support growth, learning and development.

- Daily decisions and caregiver actions are needed to improve IYCF practices.

- In the community, there may be existing social norms that undermine good nutrition practices, including the view that caring for children is a woman’s responsibility.

- Exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life and continued breastfeeding until two years of age and beyond provides both nutrition and health benefits for the infant and mother.

- Optimal IYCF practices, including dietary diversity, meal frequency, fruit and vegetable consumption, and avoiding unhealthy foods or beverages, are vital for optimal physical growth and brain development.

- Caregivers can learn to prepare local, easily sourced, low-cost and nutrient-dense foods for complementary feeding.

- Infant and child malnutrition is harmful and affects child survival, growth, brain development, life-long learning and economic potential.

- The many benefits of breastfeeding far outweigh those available from infant formula and breastmilk substitutes.

- The quality and nutritional value of locally available foods can support child growth and IYCF practices.

- Caregiver capability and self-efficacy should be used to promote confidence and motivation toward making behavioural changes.

SBCC can also be employed to complement legislative and policy initiatives to promote large-scale change, acceptance and community engagement. For example, SBCC has been used to support improved IYCF practices; inform people about the harmful effects of soda to gather support for a soda tax; encourage behaviour adoption when used in combination with conditional cash transfers; and empower young people to engage with policymakers on improving food environments.

Using the Capability, Opportunity, Motivation – Behaviour (COM-B) Model to design a social behaviour change campaign

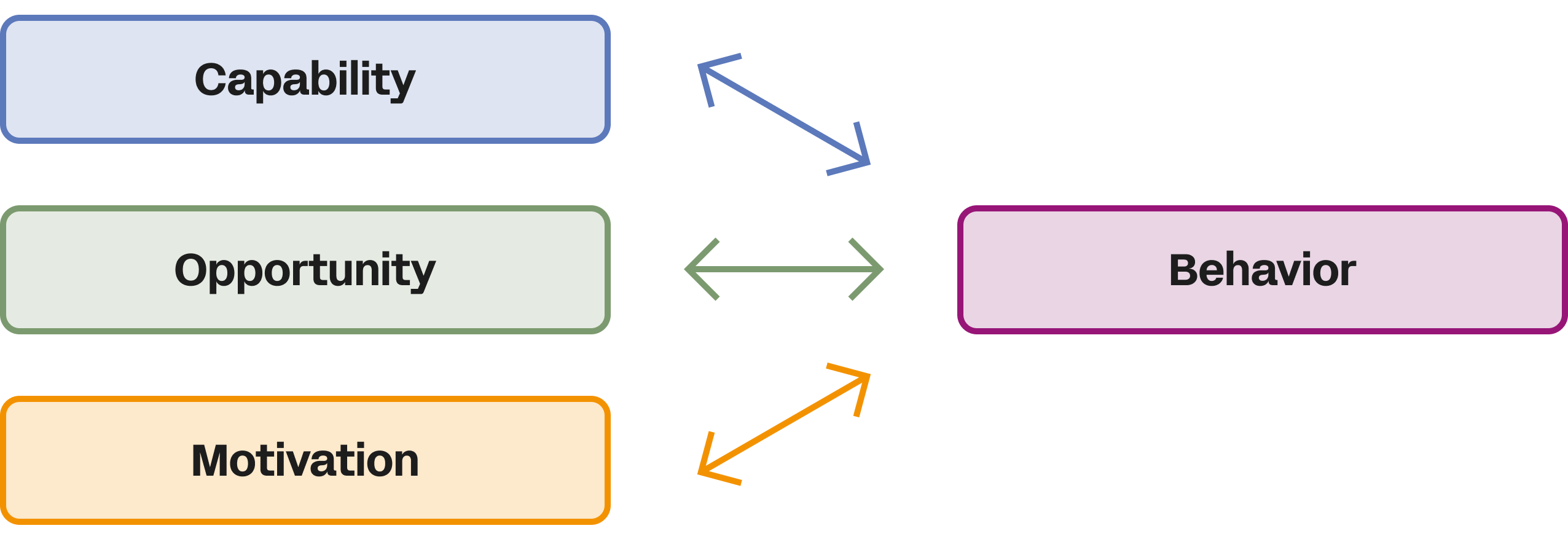

Numerous behaviour change models have been proposed and applied in nutrition programming. The design of this toolkit is based on the COM-B Model, which is classified as a ‘behaviour system’. Capability, opportunity and motivation are the three model components that both influence and are influenced by behaviours. Capability and opportunity may also both influence an individual’s motivation for behaviour change (18).

Capability is the ability, both psychologically and physically, to engage and participate in an activity. It includes the psychological elements of knowledge, reasoning and thought processes, as well as the physical skills and ability to complete a task. An example may be whether or not a caregiver knows when to introduce solid foods to an infant.

Opportunity involves the factors that occur outside the individual that prompt or enable the behaviour. It includes environmental factors like accessibility, availability and affordability, as well as social factors, including beliefs, social norms, customs and culture. An example may be the type of foods fed to an infant based on availability, local customs or culture.

Motivation is the brain processes that support and direct behaviour beyond only conscious decision-making. Motivation includes automatic responses like habits and emotions we may not think about or be aware of. It also includes reflective responses like evaluation, planning and intention to act. An example may be whether the caregiver remembers to introduce and regularly feed an infant solid food when it was not part of their routine as the infant was younger.

To effectively apply this model in SBCC, it is critical to identify a behaviour target and consider which parts of the behaviour system – capability, motivation, opportunity – would need to be altered, changed or adjusted to modify the behaviour. In addition, we must consider how the components interact with one another. For example, if a behaviour is too difficult or is constrained by environmental or social barriers, an individual may not be motivated to change.

The full impact pathway for an SBCC campaign using the COM-B model can be found in the Monitoring and Evaluation section.

The COM-B Model has been applied across different types of behaviour change research and programming. Here are some nutrition-focused research examples below.

McClintic et al. researched child nutrition in Kenya and found caregivers had the knowledge and skills to implement behaviours but were constrained by time, competing priorities, limited food availability and accessibility, poor self-efficacy for exclusive breastfeeding and held cultural beliefs around specific foods. They concluded that a lack of knowledge and skills may not be the primary influencers of IYCF practices but suggested interventions should address underlying social, cultural and environmental factors that contribute to decision-making.

Porter et al. explored the impact of COVID-19 on the eating habits of families. Parents had both the capability and motivation to provide healthy food for their families, but they faced opportunity challenges, including time, access to resources and environmental stressors. They suggested that programmes should be contextually relevant and sensitive to the contextual factors that influence caregiver decision-making.

Russell et al. focused on infant feeding beliefs and behaviours of mothers with limited educational attainment. Motivational factors and social influences were major drivers behind mother’s infant feeding practices, including breastfeeding is difficult and painful, infants will decide when to wean from breastfeeding and some infants may be ready for solid food before six months. Social influences that shaped infant feeding practices included advice from social networks, family members, books and internet resources. A mother’s receptiveness to messaging was also dependent upon her experience, beliefs and experiences with other children.